Recently, I was watching a YouTube video. When I watch anything, I usually have subtitles on even if it’s my native language. I was watching this video and vibing with the video until I saw the word “estàs” with a grave accent. It was that moment when I realized that that was a language I never studied before: Catalan. That got me thinking about the fluidity of languages. I understood the subtitles; I could read something I never learned. What does this say about the borders between languages? Having studied French and Spanish and being a native of English, which has a huge amount of Romance vocabulary, I had the tools to comprehend Catalan. To understand this, we must realize that language has no borders.

In our current world, borders between everything are so strong. Languages are a perfect example of that. Reality is different from our conception. It is false to think that every language is completely unique and have essential differences from its neighbors. The world of languages is so much deeper than that.

The modern nation-state informs our modern concept of distinct languages

Most people’s understanding of what a language is has a strong overlap with border of a nation. Our conception of the modern nation-state is part of the reason many people think this. When you go to Germany, people speak this thing called German. From the northern areas near Denmark to the southern areas near Austria, people share a system of speech. Then, when you cross the border into Austria. Something distinct happens with people’s speech. This is a huge oversimplification.

The overlap between language and national borders is relatively new in the grand scheme of things. Languages are extremely fluid things, and the borders between nations cannot match with the borders between languages. Sometimes, speakers can share a country but have a difficult time understanding each other. Other times, speakers that live 50 kilometers apart with an international border between them can understand each other perfectly. Language has no borders and does not care about our national boundaries.

Medieval Europe didn’t have “nations” and therefore “languages”

In history, humans mostly existed in groups of a few dozen, and it is likely that they couldn’t travel far before it became difficult to understand other group’s style of speech. With agriculture settling people down, many people could only understand the people only in the nearby towns. That meant you could understand the people in your village and maybe the nearby villages, but the farther you got, the weirder people spoke. They formed dialect continuums, where Person A can understand Person B, and Persona B can understand Person C, but Person C cannot understand Person A.

Dialect continuums are very typical of earlier agricultural societies. People didn’t travel far, so people only communicated to the people in the nearby villages if they ever left their villages. Nation-states as we know them did not exist, but the language people spoke were no more or less fluid because language has no borders.

Like most things, Louis XIV started this whole thing

The surprising progenitor of a quite few of our modern trends, Louis XIV of France consolidated his nation-state, and he had to therefore consolidate the language spoken, which was less intelligible across his whole realm.

Ever since classical Rome, the descendants of those speaker slowly diverged more and more. In a process similar to biological evolution, isolated populations slowly start to build up speech changes that accumulate over time until groups that once had been speakers of the same language become totally unintelligible. As such, people in the south of Louis’s kingdom spoke something quite distant from his own language. As such, consolidation of legal codes and the erasure of local traditions was part of the process of building a stronger centralized state. Where there once was spoken Occitan or Catalan, French was slowly encouraged and local varieties discouraged. This new nation-state needed to spread the idea that your way of speech is not just another descendant of Vulgar Latin; you are speaking French wrong.

The current organization of our world with nation-states having unique cultures, which include language, is a very new concept in relation to history. Tom Nicholas made a great video on the history of the nation-state. The creation of the modern world with of rights and the public sphere and nations defined by shared features led to this new era of language where languages need to be carefully defined and maintained. Therefore, to create a nation meant to manufacture a standard variety of the language where there were only vaguely related dialects before.

Germany and Italy, late to the nation party, were also late to the language party

French is pretty centralized, and English is pretty centralized. Therefore, most European languages experienced this, right? If we look at the later members of the nation-state party, we’ll see their languages missed a large amount of time to centralize as well. Spain, Portugal, France, Russia, and Britain centralized earlier. Germany and Italy unified in the 19th century. You’ll notice that these languages have huge regional differences. That’s because they’ve only been united for around 5 generations. It takes a long time for languages to erase regionalisms. When these places have no borders, it is easier to understand the idea that language has no borders.

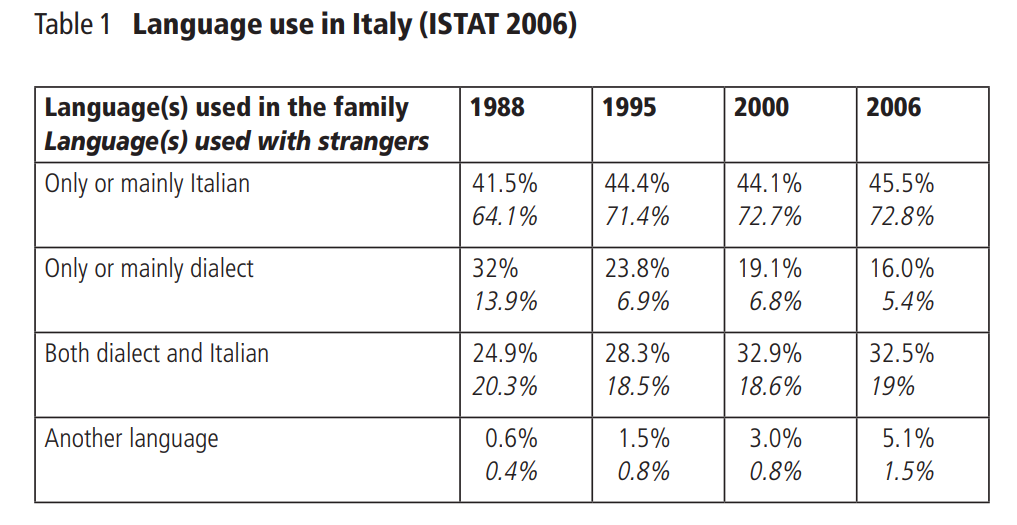

While people may speak German and Italian in everyday life, still a significant portion of the population might speak another intelligible language at home, that intelligibility being debatable depending on the language. A study by ISTAT in 2006 found that only 45.5% of Italians spoke only or mainly in Italian within the family.

This would be like Americans speaking American English at school and speaking Dutch at home. Italians are not a nation of immigrants. People didn’t move to the new nation of Italy; the new nation of Italy moved to the people. This tells us that, whether implicitly or explicitly, the public sphere and the participation in the nation-state encourages the abandonment of traditional local speech varieties.

Eastern European languages that did not have the same nation-building history do not have the same linguistic distinctions

If English and French have been successfully centralized, and Germany and Italian are partially on that path, Slavic languages show us the decentralized languages of Europe.

I speak Bulgarian at home. I don’t have an issue understanding anyone who was born within the borders of the Bulgarian Republic. One day, I was serving customers in my customer service job, and I heard some customers speak something I fully understood. They were discussing what coffee to buy. I butt into their conversation and said in Bulgarian, “Excuse me. Are you guys Bulgarian?” He then responded, “No, brother. Macedonian.”

He ordered fully in Macedonian, and I understood every word. Some vowels sounded different from what I was used to. When he said the number of his table, I did not understand him at all. Other than these exceptions, we communicated perfectly fine. In the same way that New Yorkers can communicate with Alabamans if both avoid some regionalisms, Bulgarians and Macedonians could communicate perfectly.

Because of historical forces that are way too complex to describe in a few paragraphs, the languages of Eastern Europe mostly did not experience the same nation-building projects that Louis XIV, Robert Walpole, or Otto von Bismarck brought to their countries. Eastern European nations switched from sphere of influence to sphere of influence, where each power influenced division rather than conscious assimilation to a greater nation. As such, Serbs can understand Croats, Slovaks can understand Czechs, and Bulgarians can understand Macedonians.

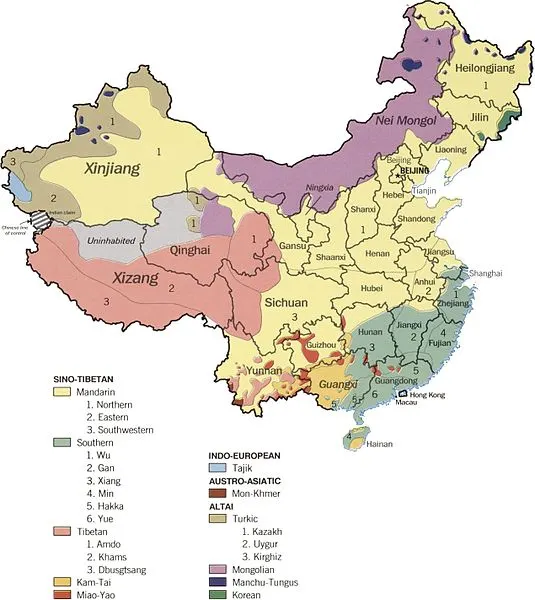

China shows us that languages can diverge for hundreds of years, but can be reunited under one dominant language in recent years

China has a similar situation to western Europe. Most of its languages (or “dialects”) descend from Middle Chinese, which was spoken in classical China. Those language diverged in isolated populations throughout the centuries to the point of being unintelligible. While many people may be within the boundaries of the nation, their speech is not identical because, again, language has no borders. To this day, the linguistic diversity in China is very impressive. However, government initiatives and advantages encourage the whole country to learn Mandarin. Recently, the Chinese version of Tiktok gave 10 minute bans to some creators for using Cantonese during livestreams. While people can still speak their local language on the street and at home, there is a trend that local varieties are disappearing from some systemic disadvantages. Younger generations are speaking Mandarin more and their local varieties less.

Looking at China, we can see how diverging languages can again converge into one of the sibling descendants. The European equivalent would be western Europe to lose their local varieties of Catalan, Occitan, Portuguese, Spanish, etc. in favor of French. This is a unique position because the abandoned and adopted languages are related. Speakers bring the local accent and some vocab preferences because there are some parallels.

You cannot have both a strong central government and linguistic diversity

There is a reason that nation-builders tried to centralize their language. Inherently, linguistically unified countries can be more efficient. There are less government documents to translate and more social cohesion. That’s not to say they are inherently better. I have no preference or recommendation. As a polyglot, I love multilingual nations. Canada, Belgium, and Switzerland, among others, are multilingual nations and functional. However, it is self-evident that a nation with one language is more united.

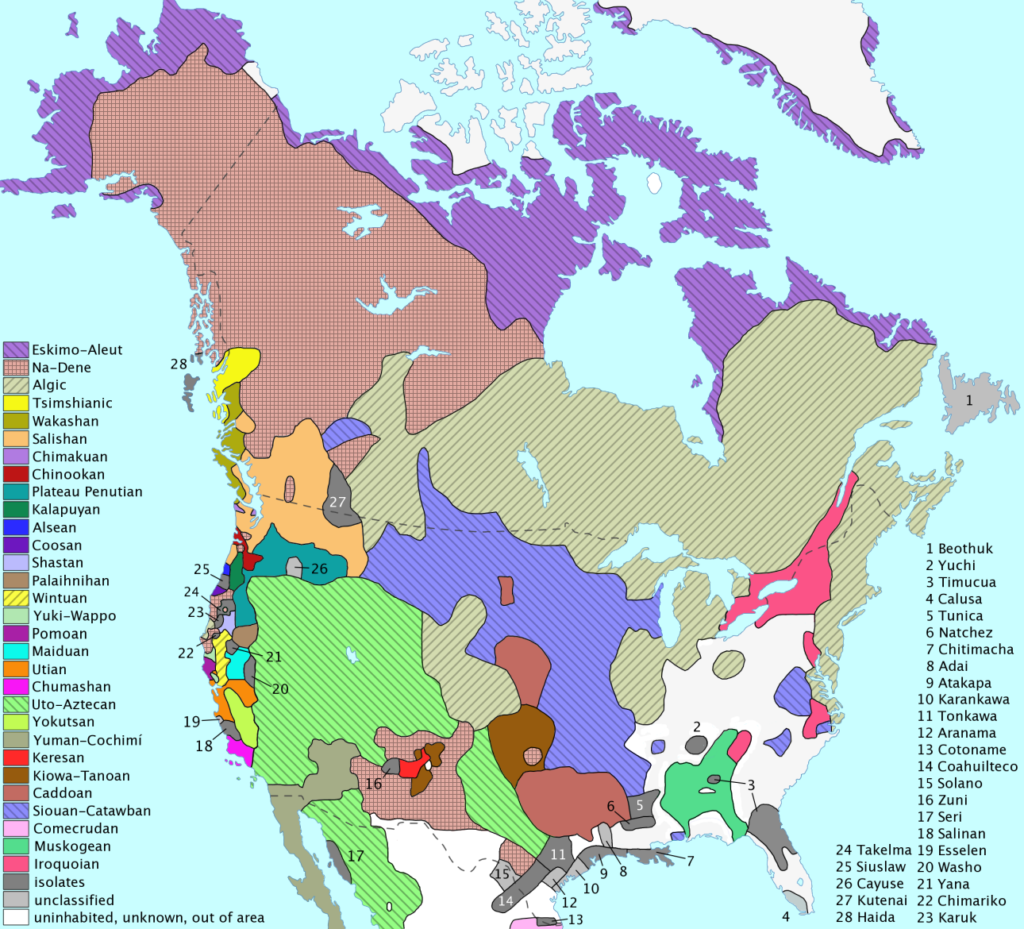

There is a trade-off. While you can improve government and business efficiency, you must give up cultural heritage. Local languages are a part of the people’s culture, and the erasure of unique varieties will erase part of human culture. It cannot be understated how much cultural heritage has been lost to the world with the subjugation and forced assimilation of First Nations’ peoples. Too many of their unique linguistic features and unique perspectives of the world are gone. We have permanently lost part of our human linguistic history. This is more than a tragedy.

Where the future goes, we can assure that consolidating power means reducing linguistic diversity

In the modern US, some regional varieties of English are disappearing. Some accents have assimilated to the general American accent, and native languages are going extinct. At this moment in time, Americans region is less a part of their identity than earlier in the nation’s history. We cannot know where it goes in the coming decades and centuries. What we do know is that when Americans define themselves on the basis of regional identity and language is when separatist feelings will return.

Language has no borders. Who is included and who is excluded is always unclear and a matter of history. The reason I was able to work on the very different East Asian languages, as I have talked about in a blog post before, was because of the weak borders between languages. The grammar and vocab may be different, but they share common structures or cognates.

As language learners, we should use the similarities of languages in our studies. Although governments will claim their languages are totally separate, you can use your knowledge of one to help the other. Cognates and similar structures can help us learn new languages faster. Just because what you’re learning has another name does not mean you need to learn from scratch. Human language is so much more complicated than unique combinations of vocabulary and grammar. We are one human race, and our languages have an unclear overlap.